AMI Historical Society & Museum

The Anna Maria Island Historical Society Museum was origi

The Anna Maria Island Historical Society Museum was origi

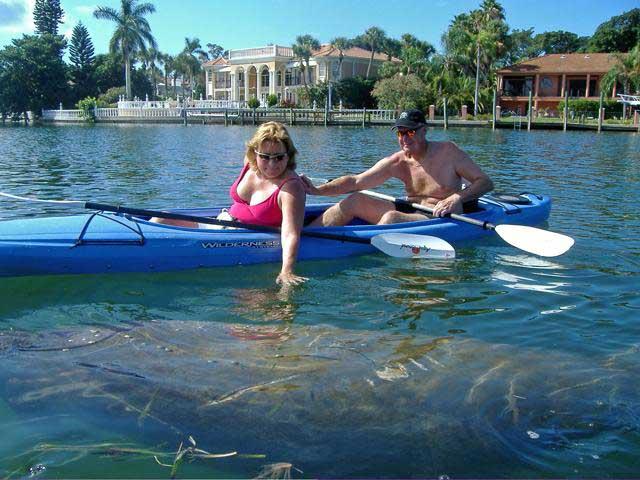

Kayak Tour will take you in and around Anna Maria Island

Visitors can enjoy the natural side of Anna Maria Island and Holmes Beach by visiting one of its many parks or public beaches.

Visitors can enjoy the natural side of Anna Maria Island and Holmes Beach by visiting one of its many parks or public beaches.

Anna Maria Island has 2 fishing piers with restaurants, 3 public beaches with picnic tables, near by public tennis courts, a playground, Community Center, Island Players Theater & the Island Branch of the Manatee Public Library. There are many fine shops, and also the Anna Maria Island Historical Society and Museum.

Waterfront restaurants serve a wide variety of food and drink. The Sandbar Restaurant on Anna Maria Island is a popular destination for beach side weddings.

Vacationing on Anna Maria Island is one of Florida's best kept secrets. For a beach vacation directly on the Florida gulf shore, visit Whites Sands Beach Resort.

Vacationing on Anna Maria Island is one of Florida's best kept secrets. For a beach vacation directly on the Florida gulf shore, visit Whites Sands Beach Resort.

White Sands is located directly on the beach, on one of Florida's barrier islands. Beautiful clean beaches filled with power fine white sand makes for a perfect day on the beach. White Sands Beach Resort has a heated pool, and 1-3 bedroom apartments vacation hotel rentals. Each apartment is fully furnished with a full sized kitchen, private bath, and large flat screen TVs and DVDs.

For more privacy and relaxation, Tropical Breeze Beach Club's cottages and motel efficiencies are just a few steps away from the gulf shore. These are two of Anna Maria Islands fine family style beach resorts that offer higher standards for cleanliness, comfort, amenities and safety.

Anna Maria Island has a free Trolley Service that travels daily up and down the island between Anna Maria Island and Coquina Beach, from 6AM- 10:30PM, about every 20 minutes. It is a cool ride on a hot day. About every 2-4 blocks there is a Trolley Stop, most have covered seating while you wait.

Anna Maria Island has a free Trolley Service that travels daily up and down the island between Anna Maria Island and Coquina Beach, from 6AM- 10:30PM, about every 20 minutes. It is a cool ride on a hot day. About every 2-4 blocks there is a Trolley Stop, most have covered seating while you wait.

Anna Maria Island is well off the beaten path. It is perfect for getting as far away from the stresses of everyday life, yet be surrounded with all the comfort and conveniences one needs.

Anna Maria Island is well off the beaten path. It is perfect for getting as far away from the stresses of everyday life, yet be surrounded with all the comfort and conveniences one needs.

Anna Maria Island is my special place for vacationing on the beach while I am in Florida.

These are my top 10 reasons why I prefer vacationing at Holmes Beach on Anna Maria Island. ![]()

Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea)

The Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) is the smallest of the sea turtles usually less than 100 pounds and named for the olive color of its heart-shaped shell

This is an omnivorous turtle It forages offshore in surface waters or dives to depths of at least 150 meters (500 feet) to feed on bottom dwelling shrimp, crabs, sea urchins and other animals crustaceans, mollusks and tunicates.. Olive Ridley are sometimes seen feeding on jellyfish in surface waters.

The Olive Ridley is found in the tropical waters of the northern Indian Ocean, the eastern Pacific Ocean, and in the eastern Atlantic along the coast of Africa. In the western Atlantic, most nesting occurs in Surinam along a short stretch of beach. The Olive Ridley has never been reported in Florida. Most populations nest on mainland shores near the mouths of rivers or estuaries and, therefore, are closely associated with low salinity and high turbidity water.

Nesting

An average clutch size is over 110 eggs which require a 52 to 58 day incubation period. The olive Ridley inhabits tropical and subtropical coastal bays and estuaries. It is very oceanic in the Eastern Pacific and probably elsewhere too. Large arribadas of olive Ridley's still occur in Pacific Costa Rica, primarily at Nancite and Ostional and Pacific Mexico at La Escobilla, Oaxaca.

The Olive Ridley was once thought to be a solitary nester. Large flotillas occasionally were reported by passing ships or along coastlines but their destination was unknown. In the 1970's, however, it was discovered that, like the Kemp's Ridley, some populations of Olive Ridley synchronize their nesting in mass emergences or ariibadas. Thousands and even tens of thousands of Olive Ridley ; nested during arribadas that would continue for several nights. Today Olive Ridley's nest in relatively large numbers on a few protected beaches but most populations have collapsed as a result of over exploitation of egg and of skins for the leather trade.

Leatherback Sea Turtle, Dermochelys coriacea

Leatherback Turtle, (Dermochelys coriacea) Dermochelys, loosely translated, means "skin-covered turtle;" coriacea means leather-like, hence the common name of the leatherback turtle. It is the largest of all the turtles, the leatherback, can weigh more than 900 kilograms (almost 2,000 pounds) and reach a length of more than 2.5 meters (8 feet).

The shell lacks the scales or shields of other turtles and is covered by a firm, leathery skin, with seven ridges or keels running lengthwise along the back. Color is usually black with white blotches. The carapace is an elongate oval, somewhat pointed toward the rear.

The endangered leatherback turtle is the largest and most active of the sea turtles. They travel thousands of miles Leatherbacks have been sighted as far north as Labrador in the Atlantic and Siberia in the Pacific, dive thousands of feet deep A leatherback fitted with a time-depth recorder made a dive of more than 3,300 feet off the Virgin Islands. In other studies over a ten-day period, the average depth of all dives of a leatherback was 222 feet and in some cases the animal was submerged as long as 27.8 minutes. The tagged female leatherback averaged 2.7 dives per hour during daylight and 3.6 dives each hour (average) at night, and venture into much colder water than any other kind of sea turtle. Up to eight feet in length, these huge turtles have a rubbery dark shell marked by seven narrow ridges that extend the length of the back.

The leatherback is the champion of sea turtles. It grows the largest, dives the deepest, and travels the farthest of all sea turtles. The largest leatherback ever recorded was almost 10 feet (3 m) from the tip of its beak to the tip of its tail and weighed in at 2,019 pounds (916 kg). The leatherback is the only sea turtle that lacks a hard shell. It is named for its large, elongate shell which is composed of a layer of thin, tough, rubbery skin, strengthened by thousands of tiny bone plates. Seven narrow ridges run down the length of the carapace, which is typically black with many white spots. The lower shell is whitish to black and marked by 5 ridges. The body of a leatherback is barrel shaped, tapering at the rear to a blunt point. With this streamlined body shape and the powerful front flippers, a leatherback can swim thousands of miles over open ocean and against fast currents.

Leatherbacks approach coastal waters only during breeding season. Nesting occurs throughout the Caribbean, on the northern coast of South America, the Pacific Coast of Central America, and on the east coast of Florida. Nesting season runs from March through July. Leatherbacks nest every 2 to 3 years, laying 6 to 9 egg clutches in a nesting season. Each clutch contains approximately 80 fertilized eggs the size of billiard balls and 30 smaller, unfertilized eggs. There is an average of 10 days between nestings. The eggs incubate for approximately 65 days.

A leatherback turtle cannot be confused with any other animal. Hatchlings are marked by white stripes and the foreffippers are as long as the shell. Adults have a smooth, scaleless black to brown shell raised into seven narrow ridges that extend the length of the back. The limbs, head and back are often marked by white, pink or blue blotches. The rubbery top shell has a thick layer of oily, vascularized, cartilaginous material, strengthened by a mosaic of thousands of small bones. The softer lower shell is whitish to black and marked by five ridges. The smooth transition between the two shells gives the leatherback a barrel-like appearance. Unlike other sea turtles, the leatherback has no claws on its flippers.

Powerful front flippers make the leatherback a strong swimmer, capable of traveling thousands of miles over open ocean and against fast currents. The keels on the carapace and the smooth transition between the head, limbs and shell streamline the body for cutting through the water. The coloration of the leatherback, dark above and lighter below, is typical of open-ocean inhabitants.

Leatherback turtles feed on soft-bodied animals such as jellyfish and ctenophores (such as comb jellies). It is said that leatherback turtle meat may also cause poisoning in humans because of the diet of jellyfish.. ingestion of plastic bags and egg collecting are reasons for mortality and population declines.

Leatherback turtles eat soft-bodied animals such as jellyfish. Jellyfish are an energy-poor food source because they are mostly water, so it is remarkable that a large, active animal can live on this diet. Small animals found in association with jellyfish such as crabs may supplement the diet, but it is not known if these items are actually digested. Young leatherbacks in captivity can consume twice their weight in jellyfish daily. Food is sucked into the mouth by expand ing the large throat. The leatherback's jaws are scissorslike and the mouth cavity is lined with stiff spines that project backwards and aid in swallowing soft prey.

The leatherback turtle is found throughout the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, from as far north as Labrador and Alaska to as far south as Chile, the Cape of Good Hope, and the southern end of New Zealand. The leatherback is known to travel as far as 5,000 kilometers (3,100 miles) from its nesting beaches. It was once thought that the leatherback spent most of its life far out at sea, but it is now known that in the U.S. it also inhabits relatively shallow waters along the northern Gulf of Mexico, the east and west coasts of Florida and north through coastal New England. Nesting occurs on tropical and subtropical mainland shores, especially in New Guinea, Indonesia, Central America, the Guianas, and the southern Pacific coast of Mexico. Many of the major nesting areas have been discovered only within the last 20 years. Estimates of the number of breeding female leatherbacks in the world range from about 70,000 to 115,000. The number of leatherback nests recorded in Florida has ranged from 38-188 since 1979.

The frequency with which leatherback turtles are seen in northern waters suggests that they regularly migrate north in search of large concentrations of jellyfish. The presence of active, healthy leatherback turtles in cold regions is of interest because, as reptiles, their body temperature would be expected to be close to that of the water around them.

Active leatherbacks have been reported at water temperatures below 60 degree; no other reptile is known to remain active at this temperature. Leatherbacks can live in cold water because, unlike most other reptiles, their body temperature can be as much as 80° higher than that of the environmental In addition to retaining heat produced by muscular activity, leatherbacks may be able to actively regulate their temperature.

The leatherback can dive to great depths. Turtles equipped with depth recorders dove to over 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) deep. This depth exceeds that reported for any air-breathing vertebrate with the possible exceptions of sperm whales and elephant seals. The shallowest dives occurred at dusk and the deepest at dawn. These leatherbacks were probably feeding on jellyfish that concentrate below 600 meters (2,000 feet) during the day and move into surface waters at dusk. The turtles dove almost continuously with only brief intervals at the surface to breathe.

The leatherback does not have a rigid breastbone or lower shell like other sea turtles so the chest may collapse during deep dives. The large amount of oil found in leatherbacks may help prevent decompression problems during diving and resurfacing.

Though Leatherbacks nest only on tropical shores. Leatherbacks nest from February through July in the West Indies, Central and South America and Florida.

Leatherbacks are also endangered, but a few nest on the east coast of Florida each year About 100 to 200 leatherback nests are recorded in Florida each year.

The leatherback turtle migrates between the cooler, open ocean waters that support the jellyfish on which it feeds and the subtropical and tropical beaches where the sand is warm enough to incubate its eggs. Studies in the Virgin Islands have shown that leatherbacks begin nesting within a week of arriving from temperate latitudes. Mating must take place before or during migration to the nesting beaches because there does not seem to be enough time to mate and develop eggs off the nesting beach.

Leatherbacks prefer beaches with a fairly steep slope adjacent to deep water. These high energy beaches are often subject to erosion, but this topography makes the beach accessible and shortens the haul to dry sand above the high tide mark. Leatherbacks are rarely seen around reefs and rocky areas where their skin could be easily cut. Even the crawl up a sandy beach can be enough to abrade the turtle's tender skin and cause bleeding.

Hawksbill, Eretmochelys imbricata

The hooked, beak-like jaws give this turtle its common name. The generic name, Eretmochplys, means "oar turtle," from the way it swims, and the specific name, imbricata, means "overlapping" because the shields on the carapace overlap like tiles on a roof.

The hawksbill is one of the smaller sea turtles, Hawksbills usually range from 30 to 36 inches in length and weigh 100 to 200 pounds. The record is 280 pounds. The thin shields overlaying the bones of the carapace, also known as "tortoise shell," are beautifully marked with amber and reddish tones with shadings to yellow, white, black and green. The plastron is whitish-yellow, occasionally with a few black splotches. The young tend to be black to brownish-black, with touches of light brown. The body has an elongated oval shape; the head is quite narrow. As with green turtles, there are four pairs of costal shields on each side of the central plates on the carapace. The shields overlap, with the exposed edges rough and serrated. The limbs usually bear two claws.

The endangered hawksbill has been hunted to the brink of extinction for its beautiful shell, which are used to make jewelry and other products.. Once relatively common in Florida, these turtles now nest here only rarely. Hawksbills feed on sponges and other invertebrates and tend to nest on small, isolated beaches.

Hawksbill turtles nest from April through November in Mexico, the West Indies and the Caribbean coast of South and Central America. Occasional nests are found on Florida beaches. In recent times a few nests have been documented in the Keys, in Palm Beach and Martin counties and at the Canaveral National Seashore, and south of Port Everglades.

Although they are found in U.S. waters, they rarely nest in North America. Hawksbill turtles nest at intervals of 2, 3, or more years. An average of 2 to 4 egg clutches are laid approximately 15 days apart during nesting season. An average of 160 eggs per clutch are laid and they incubate for approximately 60 days. Although they nest on beaches throughout the Caribbean, they are no longer found anywhere in large numbers.

Hawksbills are reported to eat a wide variety of invertebrates, but the predominate food item in most parts of the world appears to be toxic sponges. This is a very unusual diet because the sponges are made up largely of tiny, grass like needles. No adaptations have been discovered that would explain how a hawksbill turtle can Even on this diet. The tiny needles are routinely found embedded in the walls of the intestines but appear to cause no harm. In some parts of the world, hawksbill turtle meat is reported to cause food poisoning in humans because of the toxic sponges they consume.

The hawksbill may be the most tropical of all marine turtles. Although they occasionally stray into colder water, hawksbills usually are found in coastal reefs, bays, estuaries and lagoons of the tropical and subtropical Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. nesting in Florida, Mexico, the West Indies and the Caribbean coast and islands of Central and South America.

Hawksbill turtles are observed regularly by scuba divers on reefs off the Atlantic coast of Florida and in the Florida Keys and may be more common in these coastal waters than previously thought. Hawksbills can climb over reefs, rocks and rubble to nest among the roots of vegetation on beaches that would be inaccessible to larger, less agile sea turtles. Small, isolated beaches, often on offshore islands, are favored nest sites. Most nesting is by solitary females on scattered islands and shores but this may be because populations have been reduced.

Green turtles, Chelonia mydas

The "green" in green turtle refers to the coloration of its body fat. It is listed as endangered in Florida. The species has been harvested for centuries for food, but now is threatened with extinction. Green turtles usually grow to 40 inches and weigh from 300 to 350 pounds; 850 pounds have been reported. Compared to other sea turtles, the head is small relative to body size. The upper shell of adults ranges from light to dark olive-brown, sometimes with darker radiating streaks on each shield of the carapace. The plastron below is yellowish. The carapace is black to gray on very young green turtles, and the plastron dusky white. The shell is oval in outline. There are four pairs of costal shields on each side of the central row of plates on the carapace. The paddle-like limbs have a single claw

They nest mainly from July through September in the West Indies, Mexico, South and Central America, and on the east coast of Florida.

Green turtles nest on Ascension Island in the south central Atlantic Ocean from January through April. They then head westward to Brazilian waters, traveling more than 1500 miles to favored feeding grounds.

Green sea turtles are perhaps the most famous travelers, migrating great distances. A yearling green turtle tagged and released at Bahia Honda in the Florida Keys in October 1967 was retaken off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina 13 months later, having traveled more than 800 miles. Other Florida-tagged green turtles have been found in Brazilian waters. Green turtles are reported to be strong swimmers, capable of speeds of 0.88 to 1.4 miles per hour. As noted previously, one population of greens is known to nest on Ascension Island and return to the coastal waters of Brazil as their major feeding grounds.

Adult green turtles feed on sea grasses and algae, though very young greens are more carnivorous feeders. One of Florida's seagrasses, Thalassia testudinum, has the common name of "turtle grass" because green turtles graze in the submerged meadows.

Green sea turtles are perhaps the most famous travelers, migrating great distances. A yearling green turtle tagged and released at Bahia Honda in the Florida Keys in October 1967 was retaken off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina 13 months later, having traveled more than 800 miles. Other Florida-tagged green turtles have been found in Brazilian waters. Green turtles are reported to be strong swimmers, capable of speeds of 0.88 to 1.4 miles per hour. As noted previously, one population of greens is known to nest on Ascension Island and return to the coastal waters of Brazil as their major feeding grounds . Green turtles are the only sea turtles that eat plants. They graze on the vast beds of seagrasses found throughout the tropics. Some populations travel over a thousand miles over open ocean to nest on islands in the mid-Atlantic.

The species has been harvested for centuries for their meat and the gelatinous "calipee" that is made into soup. Hunting and egg gathering have reduced their numbers greatly, but now is threatened with extinction.

Most green turtles nest in the Caribbean but 500 to 2000 nests are recorded in Florida each year.

Green turtles usually grow to 40 inches and weigh from 300 to 350 pounds; 850 pounds have been reported. Compared to other sea turtles, the head is small relative to body size. The upper shell of adults ranges from light to dark olive-brown, sometimes with darker radiating streaks on each shield of the carapace. The plastron below is yellowish. The carapace is black to gray on very young green turtles, and the plastron dusky white. The shell is oval in outline. There are four pairs of costal shields on each side of the central row of plates on the carapace. The paddle-like limbs have a single claw.

Green turtles are an endangered species around the world, but they still nest in significant numbers on the east coast of Florida. They are easily distinguished from other sea turtles because they have a single pair of scales in front of their eyes rather than two pairs as the other sea turtles have. The green turtle is the largest of the Cheloniidae family. Female green turtles that nest in Florida average more than three feet in carapace length, and average about 300 pounds in weight. The largest green turtle ever found was 5 feet in length and 871 pounds. Green turtles nest at intervals of 2, 3, or more years. They lay an average of 3 to 5 egg clutches, with about 12 days between each nesting. There are an average of 115 eggs per clutch and they incubate for about 60 days. Nesting season runs from June through October in the U.S. The largest nesting site in the Western Hemisphere is at Tortuguero, Costa Rica.

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is named for the greenish color of its body fat. Hatchlings are dark but adults have a smooth, olive-brown shell marked with darker streaks and spots. The bottom shell is white or yellowish and each paddle-shaped flipper usually has one claw. Green turtles can be distinguished from most other sea turtles by the single pair of scales on the front of the head.

The green turtle is found in parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, primarily in the tropics. The most important nesting grounds for green turtles in the Americas are Tortuguero, on the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica, a few beaches in Surinam, and Venezuelan-owned Aves Island in the eastern Caribbean.

Roughly 60 to 800 green turtle nests are reported each year on the east coast of Florida, most of them between Volusia and Broward counties. On rare occasion nests are found on the west coast in the Panhandle area. A population of immature green turtles can be found year round in the Mosquito Lagoon portion of the Indian River lagoon system on Florida's east coast, and an increase in the number of smaller turtles suggests that this population may be growing. Mosquito Lagoon may be the northern limit of the winter range for green turtles. Immature green turtles also have been reported from the nearshore waters of Hutchinson Island, Cape Canaveral, Broward County, in Florida Bay and in the Cedar Key-Crystal River area.

Green turtles were once abundant in the waters of south Florida and the Caribbean. In 1503, on his fourth and last voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus reported that his ship came ". . . in sight of two very small and low islands, full of tortoises, as was all the sea about, insomuch that they looked like little rocks, for which reason those islands were called Tortugas." These islands, later renamed the Cayman Islands, were once the site of a large green turtle rookery.

For 300 years the vast flotillas of turtles played an important part in the exploration and exploitation of the region by Europeans, including pirates. Much of the early activity in the new world tropics was dependent in some way on turtles. Turtle meat and eggs provided a seemingly unending supply of protein, and turtles could be kept alive on ships for long voyages by turning them on their backs in a shaded area of the deck. Turtle oil was used for cooking, lamp fuel and as a lubricant.

Besides feeding the explorers and residents of the Caribbean, the green turtle was shipped to Europe, particularly England, where it was considered a great delicacy for its meat and the gelatinous "calipee," found along the lower shell that was made into soup. With the advent of steam travel, more turtles could be shipped alive. By 1878, 15,000 turtles a year were being shipped to England from the Caribbean.

The supply of turtles must have seemed endless as each year new individuals completed the long maturation process and emerged from the sea to nest, but by the early 1700s green turtles were becoming scarce in many areas. The first rookery to be decimated was that of Bermuda and then, one by one, the turtles disappeared from their nesting beaches throughout the region. The green turtles of Florida are a remnant of a much larger population that was hunted to the edge of extinction. Both nesting females and subadult turtles were hunted commercially. In the late 1890's, turtle hunting grounds extended from Marquesas Key to Alligator Light on the east coast, the Dry Tortugas, through Florida Bay and around the Cedar Key region. By the 1940's and 50's, Florida's green turtle population had been greatly reduced but Key West and other ports remained as processing centers for green turtles caught throughout the Caribbean. Although Florida's seagrass beds were once important feeding grounds, it is likely that green turtles nested in large numbers only in the Keys and the Cape Sable region.

Green turtles are found on broad expanses of shallow, sandy flats covered with seagrasses or in areas where seaweeds can be found. Scattered rocks, bars and coral heads are used as nighttime sleeping sites. Every morning the turtles head out to feed and every evening return to their particular shelter to sleep. The round trip may be several miles.

Hatchling green turtles are carnivorous; juveniles and subadults eat many things including man-o-war and jellyfish. When green turtles reach 20 to 25 centimeters (8 to 10 inches) in shell length, however, they begin feeding on algae or seagrasses on shallow flats. No one knows how old the turtles are when this occurs. Adult green turtles are unique among sea turtles in being plant eaters.

The vast beds of seagrasses found throughout the tropics serve as pastures for green turtles. Seagrass is high in fiber and low in protein. As an adaptation to this diet, green turtles maintain "grazing plots" of young leaves by feeding repeatedly in the same area. By eating young plants in the grazing plots, green turtles can avoid older leaves that are higher in fiber, and thus increase the percentage of protein in their diet.

Only adult sea turtle with diet of seagrass and seaweed. Named for greenish color of body fat. 60 to 800 nests reported each year. Medium to large sea turtle: nesting females in Florida average 3.3 feet in length and 300 pounds in weight. Hatchlings: 2 inches long. Nest in Florida from June through late September. Survival in Florida threatened by beach lighting, habitat alterations and drowning in fishing gear.

Some populations of green turtles feed on algae even if seagrass is available. Seagrasses and algae differ in their chemical composition so green turtles have specialized bacteria in their gut to aid digestion. For this reason, green turtles cannot easily change their diet when other food sources become more abundant. The young green turtles found year-round in Mosquito Lagoon eat seagrass even when algae is more abundant.

Since their diet is low in protein, green turtles grow slowly and sexual maturity is delayed. In captivity on a high-protein diet, green turfles can mate and lay eggs in 8 to 11 years. This diet also results in more nests per season and a shorter interval between nesting seasons as compared with wild turtles. It has been estimated that green turtles in the wild may not reach maturity until 15 or even 30 to 50 years of age. Dramatic variations in growth rates have been observed from one feeding area to another, and the differences have been attributed to food quality and temperature. Green turtles have a constant and plentiful source of food with few competitors, but the trade-off is that their growth rate and reproductive output are lower than if their diet were more nutritious.

One of the most intriguing aspects of green turtles is their ability to travel long distances and locate specific sites with remarkable precision. Caribbean turtle fishermen have many stories about capturing a distinctive green turtle, shipping it hundreds of miles to market in Key West where the turtle was washed out of its holding pen in a storm, and then recapturing the same turtle under the same rock as before. Green turtles are as loyal to nesting sites as they are to preferred feeding grounds or sleeping rocks. Some populations of green turtles may nest and graze in the same region and others follow coastlines from feeding to nesting grounds and back. Other populations, however, travel great distances over open water. At some Brazilian feeding grounds, several populations share the same pastures but always return to their respective nesting beaches.

One of the best-studied migratory populations feeds along the Brazilian coast but nests on Ascension Island, which is 8 kilometers (5 miles) wide and 2,250 kilometers (1,400 miles) to the east of Brazil over open ocean. We can only speculate as to why turtles would make such a difficult journey or how they can find this island in the vastness of the mid-Atlantic.

Centuries ago, sea turtles roamed our oceans by the millions. In the last 100 years their numbers been greatly reduced. All seven species of sea turtles are in danger of extinction.  Demand for sea turtle meat, eggs, and other by-products, as well as a loss of habitat, commercial fishing, and pollution have contributed to their decline.

Demand for sea turtle meat, eggs, and other by-products, as well as a loss of habitat, commercial fishing, and pollution have contributed to their decline.

Do your part to protect our sea turtles.

Loggerhead, Caretta caretta

The common name is derived from the massive, block-like head and broad, short neck of the animal. It is the only turtle in the genus Caretta and is listed as a threatened species in the United States; international trade is completely banned and the turtle is considered to be vulnerable worldwide.

Loggerhead turtles are the most frequently observed turtles in Florida waters. They are one of the largest of the hard-shell turtles, with adults measuring 36 to 38 inches in length, and a weight range of 200 to 350 pounds, but larger specimens have been reported. The upper shell or carapace is widest near the front, just behind the front flippers, then tapers toward the rear. carapace is colored reddish-brown with some yellowish touches; underneath, the plastron is creamy yellow. There are five pairs of costal shields or plates on each side of the central row of plates on the carapace. The shell margin of young loggerheads has a somewhat serrated appearance which disappears as the turtle matures. The limbs are paddle-shaped and each bears two claws.

As with all sea turtles, the adult male has a long tail; the tail of the female is short. Biology. Scales on the top and sides of the head and top of the flippers are also reddish-brown, but have yellow borders. The neck, shoulders and limb bases are dull brown on top and medium yellow on the sides and bottom. The plastron is also medium yellow. Adult average size is 92 cm straight carapace length; average weight is 115 kg. Hatchlings are dull brown in color. Average size at hatching is 45 mm long; average weight is 20 g. Maturity is reached at between 16-40 years.

Loggerheads are known to travel as far north as Nova Scotia or south to Argentina. Florida- tagged specimens have been sighted in Chesapeake Bay, in the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles and in the Gulf of Mexico. As loggerheads mature, they travel and forage through near shore waters until the breeding season, when they return to the nesting beach areas. The majority of mature loggerheads appear to nest on a two or three year cycle.

Like their cousin the tortoise, sea turtles may take their time, but they are remarkably persistent, according to new evidence from an Earth watch sponsored researcher. A satellite tag was recovered in Baja, Mexico, from the flipper of a Loggerhead sea turtle that was tagged in Japan. The tag confirms that endangered loggerheads shuttle nearly 7,500 miles (12,000 kilometers) each way across the Pacific Ocean between nesting beaches in Japan and feeding grounds off the coast of Mexico.

Loggerhead turtles are essentially carnivores, feeding primarily on crabs, horseshoe crabs, shrimp, jellyfish, and a variety of mollusks. The strong beak-like jaws are adapted for crushing thick- shelled mollusks. which they use to eat hard, shelled animals such as crabs and clams. Although loggerhead sea turtles are primarily bottom feeders, they also eat sea jellies obtained while swimming and resting near the sea surface.

Loggerhead populations in Honduras, Mexico, Colombia, Israel, Turkey, Bahamas, Cuba, Greece, Japan, and Panama have been declining. This decline continues and is primarily attributed to shrimp trawling, coastal development, increased human use of nesting beaches, and pollution. Loggerheads are the most abundant species in U.S. coastal waters, and are often captured incidental to shrimp trawling. Shrimping is thought to have played a significant role in the population declines observed for the loggerhead. Mating takes place in late March-early June, and eggs are laid throughout the summer.

Loggerheads are circumnavigators, inhabiting continental shelves, bays, estuaries, and lagoons in temperate, subtropical, and tropical waters. In the Atlantic, the loggerhead turtle's range extends from Newfoundland to as far south as Argentina. During the summer, nesting occurs in the lower latitudes, but not in the tropics. The primary Atlantic nesting sites are along the east coast of Florida, with additional sites in Georgia, the Carolinas, and the Gulf Coast of Florida. In the eastern Pacific, loggerheads are reported as far north as Alaska, and as far south as Chile. Occasional sightings are also reported from the coast of Washington, but most records are of juveniles off the coast of California. Southern Japan is the only known breeding area in the North Pacific.

Sea turtles are marine reptiles that have existed since their giant land turtle ancestors returned to the sea sometime during the Age of Dinosaurs. Eight species of sea turtles have managed to survive to modern times. Three of these extant species, the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta), the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), and the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) nest on the beaches of Broward County from April through September every year. The loggerhead is the most common sea turtle using the area for nesting; as a matter of fact, Florida, from the Space Coast to the Gold Coast, is the second most important nesting area in the world for loggerhead sea turtles.

Loggerhead turtles were found buried in silt off Palm Beach Inlet and the Indian River, and lodged in the soft muddy walls of the Cape Canaveral Ship Channel. This previously unknown activity may be a type of hibernation, or simply a way to warm themselves, since they are susceptible to hypothermia in cold water. The mud covering may also serve to rid the shell of encrusting barnacles. . . This reddish-brown turtle is named for its large head which may be 25 centimeters (10 inches) wide. Powerful jaw muscles allow the loggerhead to crush heavy-shelled clams, crustaceans and encrusting animals attached to rocks and reefs. The shell is very thick, particularly toward the back, which may serve as protection from sharks that occasionally prey on this relatively slow swimmer. It is estimated that loggerhead turtles reach maturity between 20 and 30 years of age and have a maximum reproductive lifespan of about 30 years.